Damo Jones’ debut thriller, A Singularity, is set in the near future as the ramifications of climate change take hold. The novel’s two protagonists, Selene and Mark, embark on a fraught odyssey to make a stand against what they see as the planet’s decline and the lack of urgency to combat it. The young lovers also experiment with Dreamers, innovative drugs which give users incredible adventures whilst sleeping. Gradually the real world and their dreams merge dangerously together and are lost in a place they struggle to fully understand, faced with an atrocity they may have committed as environmental terrorists. Desperate to find a way out and separated from each other, they are pushed ever closer to a terrifying climax set to a backdrop of environmental protests, sinister technological advances and rampant consumerism with many countries on the brink of societal collapse.

How would you describe Selene and Mark, the novel’s main characters?

They are both strong characters, but I think Selene’s journey is more complete. She has a deeper validation. In the early drafts it was less of a love story and even now it’s a very warped one. But the sense of their connection kept getting stronger the more I wrote about them. So it’s love at its core, but maybe deeper, symbiotic perhaps. I wanted them to have these immutable catalysts for why they do what they do. Their acute trauma draws them together, it’s what compels them to go far beyond where anyone else really would. The situation is extreme, but so are the reasons why they are who they are. They are also vulnerable and flawed and these traits are exploited by others. But they want to do good, they strive to make a difference but this drive takes them too far. Their situation starts to unravel rapidly and it becomes as much about survival and escape as it does understanding what they have actually committed, this deadly act they are part of. They have blood on their hands. They become climate change terrorists.

It’s reasonably safe to say they come from some dark places, and they go to even darker ones?

I guess that is fair to say, yes. The novel has a lot of layers, from relatively halcyon moments to extreme, diametric opposites. The flash backs and flash forwards are meant to give clues and insights as to what has happened. Some parts are interpretive too – it’s up to the reader to decide what is happening. But darkness – for sure, yes. The central question is how far would you go to protect the world you love? What would you really do to make a stand? When I sketched out the first scenes it was more experimental, it felt like a rage against the world’s condition. Selene and Mark much go further that most people ever would to combat it. So Extinction Rebellion, Greta Thunberg, global protests about the climate emergency – those sorts of things I had in mind at the start, just in different guises. Think about what would you really do, if pushed to your absolute limit, to make the powers that be notice? I think we all look around at how the world has irrevocably changed, and it is going to get a whole lot worse. There is still that overwhelming sense now, I feel more than ever, of global inertia. We are all sat on our hands and the world is spinning off its axis as it enters this new terrifying phase. Not enough is being done. The recent climate change protests led by Greta I think have been a powerful stand and a new movement gathering momentum, but I wonder what will come of this, who is going to act?

What do you think will happen next?

I am a big pessimist now. I have a young son, so children focus your thinking even more. What world are they inheriting, what world will their own children face? Their children’s children? A Singularity is kind of looking around the corner, time-wise, to maybe 3-5 years from now. But the bigger picture you can still see, day by day, of how much it is shifting and will fuck the planet in 10, 20, 30 years down the line. I think The Guardian is doing some great work on the challenge. A lot of key media are driving awareness. But politically, globally, it’s still a mess, and it just seems to move glacially when in reality the glaciers are melting faster than decisions are being made. Everything just feels a bit too late. Being pessimistic isn’t about giving up, but there is a strong feeling of what can we even do as individuals? Also anger too, the rage which comes from feeling disenfranchised. The political discourse in the UK and the USA especially has neutered the urgency of climate change for the last 3 or 4 years now, with Brexit and Trump (I should say that neither of these are actually mentioned once in A Singularity) This has obscured the true work and direction needed. So much valuable time and energy has been wasted, we need more action.

Some of the way A Singularity is written feels a bit cinematic, and it’s not formed in conventional chapters either – can you explain why?

I wrote the novel with a film’s format in mind, which means it is generally short scenes played out instead of whole chapters. It’s got three sections – the first and last are told alternately from Selene and Mark’s perspectives with the chronologies mixed up, then the central passage is a first-person perspective piece. It’s supposed to take the reader out of the moment and somewhere totally different, skewering the narrative. I had a series of scenes fixed in my head, of people in these challenging circumstances, and wrote them one by one and then slotted them all together. But the middle section is a complete change of pace, of location, of everything. I hope there’s a build-up of tension, and when there is action it is earned. I also kept thinking about Chekov’s Gun – that concept literally, because there is a gun and it gets fired – and also trying to make sure nothing is wasted or extraneous. As an example, Die Hard is one of my all-time favourite films. It’s quintessential Hollywood popcorn action, (I must have seen it hundreds of times) but all of the little links and moments at the start have meaning and resolution later.

What inspirations have helped form the novel?

Two of my favourite ever books are David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas and Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveller. They both have really interesting narrative structures and are great stories. I loved Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From The Good Squad and the way that was put together. Even Filth by Irvine Welsh, with the tapeworm popping up literally in the story. That sticks in my mind, too. I love those kinds of weird directions books can go in, and not being written conventionally. So with A Singularity I wanted it to be less linear than a normal sort of book. I used to immerse myself in the Choose Your Own Adventure series and I did Warhammer role playing for years (no dressing up in outlandish costumes though, sadly) Those books were open ended and also filled with dead ends or unfinished strands.

So part of A Singularity is about the possibilities. There’s a great play called Constellations which captured this brilliantly, it was in Liverpool a few years ago. The multi-verse, the range of futures you can potentially have, darting back and forth through time. Inception is an absolute classic, the whole idea of dreams within dreams and going into other people’s dreams. And I love films which turn into something else entirely and I draw inspiration from those, too. I mean films like Kill List (one of the best UK horror thrillers in the last decade), to From Dusk Till Dawn, Audition, The Witch, Hereditary and Midsommar which is also great. A Singularity’s themes are not so much like these films – most are visceral horror, or they end up as that – but I hope there’s the same sense of what-the-fuck a bit running through my book, of things turning irrevocably on their head. That’s important to me, to try to capture that freefall, as that is how the world feels right now.

Dreamers feel like they could be from an episode of Black Mirror. Do you agree?

It’s near-futurism really, which I think is Black Mirror’s overall theme. I have always loved this idea of controlling dreams, dreams which feels as real as being awake, but you can do so much more – experience danger, adventure, risk, pure love, thrills, peril, fly to space, fight with dinosaurs, be a spy, even die – and yet there’s no actual danger. You get to save the world which is a classic narrative. So again, in the early drafts, Dreamers and Augmented Realities were something which was already there, with billions of consumers taking them, legalised like smoking or drinking alcohol. You can take a pill and have an incredibly real, lived-in experience whilst you sleep, and exert full control in your dream like playing a vivid game. So accessing parts of our brains underused whilst sleeping, because there is so much processing power there – it’s quite sci-fi, but perhaps not that far away. This part of the book is more subtle I hope – it’s just there, it exists. It’s something established and embedded and normal, with Augmented Realities on the scale of Apple, Netflix or Amazon. Dreamers are sold as entertainment, a very addictive entertainment. It just goes awry when Selene and Mark experiment with the pills and realise they can share their dreams. That’s when things start to go wrong.

How would you describe the self-publishing process?

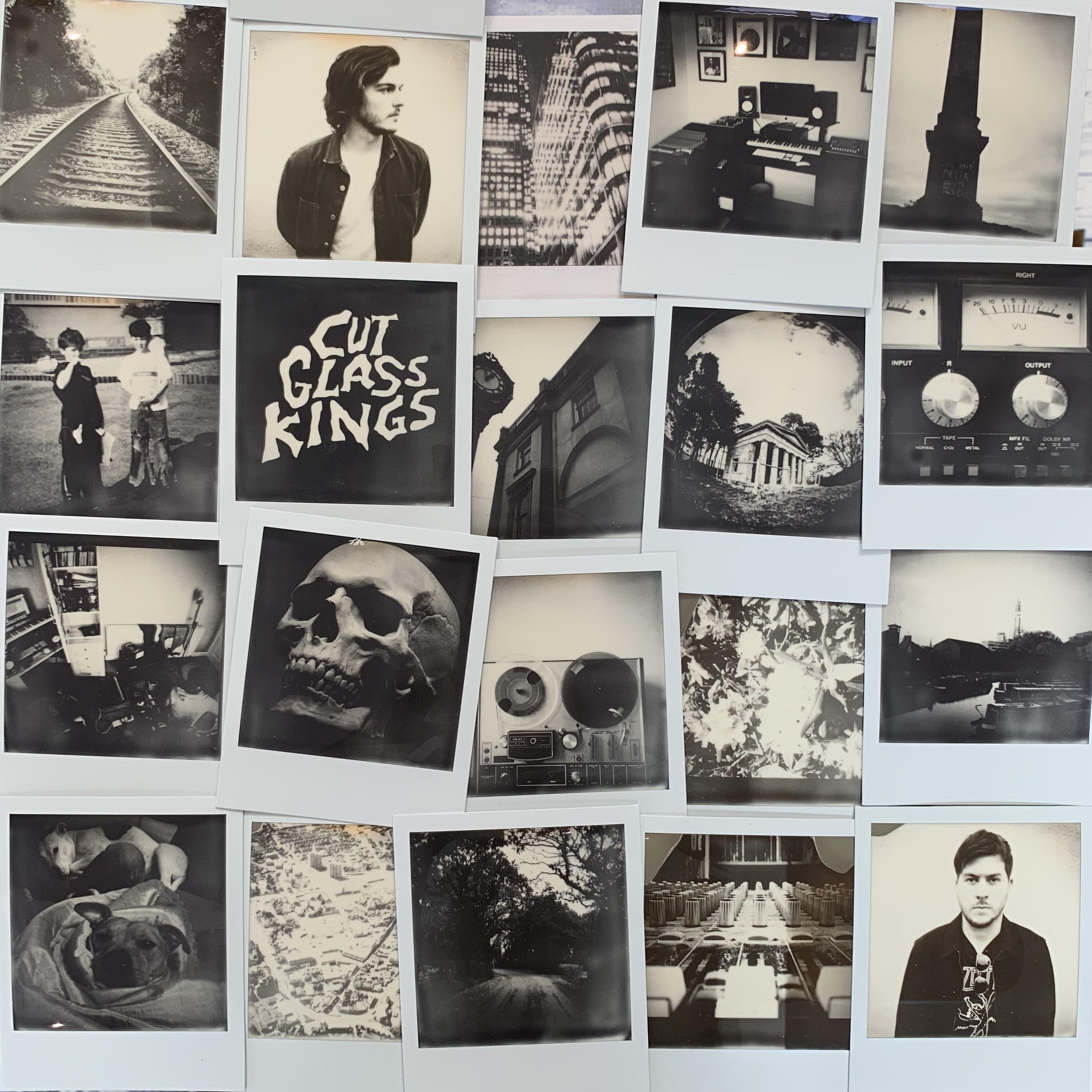

I always hoped I would be published conventionally, in all honesty, and have tried that route as far as it can go. It is really, really hard getting an agent, then the agent getting the book a deal. The process of sending out letters and material to agents can be soul-testing for sure. I love the physical, tangible nature of books, the feel of actual pages, or the way old books have that dusty scent. Yet self-publishing is good on the one hand, because it makes everything a lot more accessible for many more writers, in the same way for people making music – it’s easier to make and release music, you don’t need a record label, and can release digitally. I think the main issue though is quality. And there are so many self-published books coming out, some better than others. I have spent a lot of time polishing A Singularity, to the point of ending up feeling a bit crazy. But hopefully that final stage will show through in the text. The manuscript has had a really positive response too from the Faber Academy. They said it’s: “Brilliant… this is no ordinary book.” I will take that!

What’s next?

I am working on some new ideas. One is a short novella – it’s actually a draft I had way back in university which feels more apposite now, something around celebrity culture. Another idea will be related to A Singularity, I think in a small way at least. I am thinking of how to include parts of this in a new novel I am working on with the characters and text interlinked, maybe just tangentially. So they will live on in a different way in another book. Remember how Patrick Bateman kept popping up in Bret Easton Ellis’ novels? Also perhaps Augmented Realities too, the Dreamers. They might make an appearance as well. Let’s see. It takes a while for the ideas to brew, then they burst into writing. And there is so much happening in the world right now, so much to digest. It feels like a critical point is approaching soon, and we won’t be able to turn back after.

A Singularity is out now: https://amzn.to/2nhNGR0

Excerpt

“Can you remember anything else?” she asked cautiously.

“No. Voices, maybe, I recognise. So… you know my name. And my brother’s name. The car. You were…”

She exhaled slowly, pushing back everything she wanted to say, all that she needed to say right there and then. She contended with all the doctor had told her and the penitent rawness of that moment.

She stared at him as he lay back onto the pillows. She felt he looked right at her through the bandaging. Her eyes dewed and she shuddered, clasping her arms around her chest. His head there, swaddled, with holes for mouth and nose.

“You were there. You knew my name. Are you crying?”

She gulped drily. “No. I have to go.”

“Go where?” he said. His voice was cracked and scratchy. “Stay. Please stay. Please.”

She got off the bed in a clumsy rush and walked to the door. She turned back to regard him. He was still staring at her she was sure, one arm raised, probing. He looked tiny and frail in the room, supine on the bed by the window. Warm tears dribbled down her cheeks and she wiped dry a snotty spool with her forearms and turned and pulled the door shut.

She walked outside into the yard. The air was warm and close. In that depthless night she felt she might have been the last truth alive, her barracking heartbeat pounding into the void far above, echoing through time. She believed she could reach out to the clinquant stars winking upon that black baize and cup them all in her palms, to touch the edge of the universe and push her fingertips through its fabric into a new beyond.

She looked back up to his window.